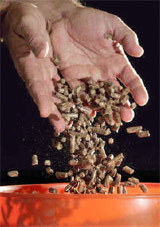

Show Me Energy Cooperative has developed a farm friendly easily portable combination energy pellet that is derived from farm waste.

Made from switchgrass, sawdust, cornstalks and hay that most cows would turn up their noses at, the greenish-brown nuggets of so-called biomass fuel offer a way to generate electricity and to squeeze more money out of farming. As a bonus, the pellets kick out less of the greenhouse gas widely blamed for global climate change.

“This isn’t going to save the world,” said Kurt Herman, a Brunswick, Mo., farmer and supplier for the Centerview plant and a member of the co-op’s board of directors. “It’s just going to save a little piece of it.”

More precisely, the plant will give farmers within about 100 miles a place to sell what often they now pay to get rid of.

The plant’s operators hope to pay about $6 million a year for raw materials from about 400 farms and then grind, heat and bind them into about $15 million worth of power plant fuel.

While much of the attention in the country is on ethanol plants — making liquid fuel from corn today, and from cellulosic material in the years to come — the Centerview plant boasts the first U.S. production of a solid biomass fuel to be burned locally.

Already, Aquila’s power plant in Sibley is running test burns with pellets blended with coal. The project is small-scale, with pellets only 3 to 5 percent of the mix to fire up just one of the plant’s smaller boilers.

The pellets are inferior to coal in a handful of key ways. Ton for ton, they contain significantly less energy than coal. They need to be kept dry or they turn into mush resembling soggy dog food. And engineers are still unsure what must be done at a plant to make them burn efficiently.

“The boilers are very sensitive to the fuel they burn,” said Jeremy Morgan, an Aquila vice president for renewable energy. “The bottom line is that the supply is equal to only a fraction of the coal we burn.”

At best, the biomass plant could send 100,000 tons of pellets annually to the Sibley Generating Station, which burns up to 2 million tons of coal a year.

Yet those running the co-op in Centerview see themselves as the inspiration for what could be scores of similar facilities across the Midwest.

“I like to say we’re sitting in the Saudi Arabia of biomass energy,” said Steve Flick, president of Show Me Energy.

He imagines a countryside dotted with plants kept close to farms and customers to keep shipping costs low.

The nuggets could be sold for home use in wood pellet stoves — a more convenient and efficient turn on traditional wood-burning stoves — and to heat poultry barns in the region.

The boon for farmers who have joined the cooperative, Flick said, is unloading otherwise unmarketable byproducts such as post-harvest remains of corn plants and other crops.

It also gives new incentive to plant perennial plants — grown without the annual corn or bean seed and other costs of most commercial agriculture. That could mean more plots of switchgrass and elephant grass, proved far better at capturing carbon in the soil.

Likewise, the biomass pellets burn in a planet-friendly way, belching up far less of the pollutants expelled by coal. For every ton of coal replaced by biomass fuel, the amount of carbon dioxide propelled into the atmosphere is reduced by nearly 1.7 tons.