A Every few minutes, Richard Wolfe poked his gloved hands into coal dust to remove a block from a pottery kiln’s viewport so he could peer at the metal 55-gallon drum inside.

A steady whoosh of 1,300-degree flames engulfed the weathered drum and its contents, the ingredients for what the scientist called “super clean” coal.

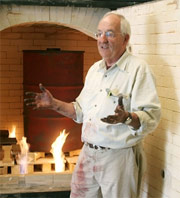

“What we’re doing is taking the coal apart and putting it back better than it was naturally,” he told his audience of four coal industry insiders who met with him on a recent Saturday in a dusty barn in Lebanon, Va.

Wolfe, the son of a West Virginia coal miner and a former Abingdon-based coal researcher now residing in North Carolina, calls the end result “carbonite,” a glossy chunk of rock that looks more like a burned brownie than coal.

He said it burns hotter than coal and can power generators that make electricity, but without spewing as much carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the air as regular coal.

The same chunk also could be used in the steel industry, home heating or even water purification.

Simply put, carbonite is the combination of two types of coals heated at high temperatures with a secret catalyst. Wolfe declined to name the catalyst because he intends to patent both the process and the product.

The byproduct of Wolfe’s kiln-based cooking process is methane gas, the main ingredient for natural gas, which often is used to fire steam boilers at electric plants. The orange-yellow methane gas could be seen through the kiln viewport rising from the drum after less than an hour into the burning process.

It’s one byproduct that can be scraped from carbonite for resale.

Gas to power cars and oil – just like the black gold shipped from the Middle East – can be extracted from the carbonite. After all, oil eventually becomes coal, Wolfe explained. What sets carbonite apart is that it produces 25 percent less carbon dioxide than natural coal, half as much sulphur dioxide and no mercury.

The gas and oil are two more byproducts to squeeze from Wolfe’s invention. And all of carbonite’s ingredients can be found in Southwest Virginia and other parts of America.

Wolfe, who runs Wolfe Engineering and Consultants in Banner Elk, N.C., researched and perfected the process in labs at West Virginia University over the last two years. He often races from his home and business in North Carolina to business contacts in West Virginia and Southwest Virginia, and sometimes shoots to Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, where he conducts more coal research and consultation.

Some companies already capture carbon dioxide on a limited scale. Once captured, the byproduct is pumped into already tapped oil fields to force to the surface the last remaining drops of oil.

America once considered coal to be the light at the end of its tunnel. The federal government funded coal-to-gas research nearly 30 years ago, but backed out after oil prices began to drop.

Wolfe thinks carbonite can beat the odds simply because it can be used in manufacturing steel and in other industries as well as in the energy game. It’s still a money-maker even if oil prices suddenly drop, he said. “We have the technology. We just need the resolve” to commercialize carbonite and create an independent America, Wolfe said.